The Path Back to Trust: How Government Accountability Journalism Respects Rather Than Lectures Its Audience

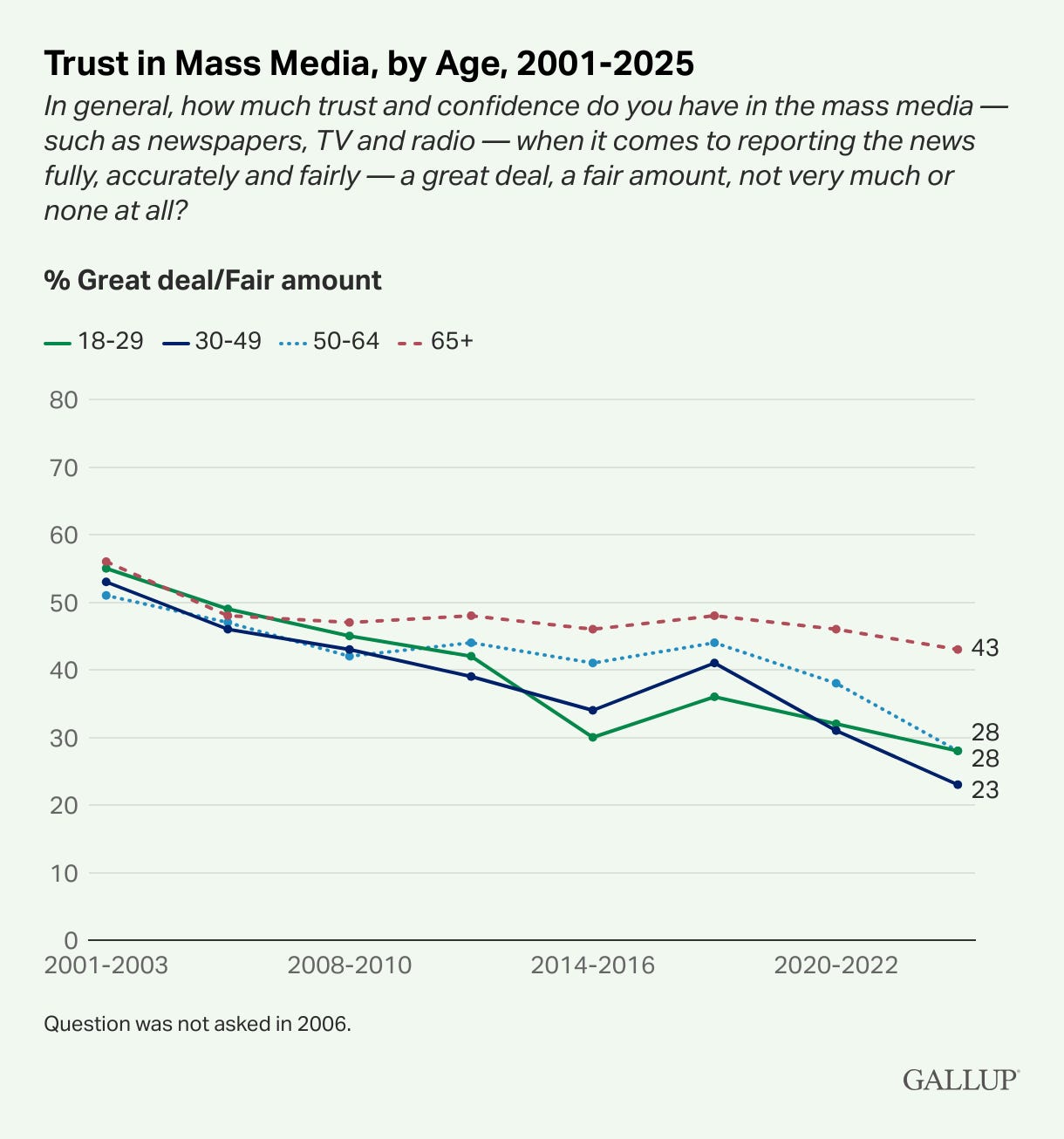

In an era when trust in news media has plummeted to historic lows, The Center Square’s six-year growth to 1,360 outlet partners across the United States offers a counterintuitive lesson: Journalism flourishes not when it tells people what to think about their government, but when it simply shows them what government is doing with their money and allows them to draw their own conclusions about those spending priorities.

Free Press Columnist Briar Dudley at the Seattle Times recently wrote about the debate over whether journalists should avoid the word “democracy” to prevent triggering partisan fatigue.

His headline captured his personal dilemma perfectly: “Save the press but don’t say ‘democracy’.” While Dudley defends the continued use of the term, his piece inadvertently highlights why so many Americans have tuned out: Metropolitan news organizations like the Seattle Times have thrown the word “democracy” around so frequently and unnecessarily that they’ve become the boys and girls who cried wolf. They’ve stripped the meaning away from the word until it has little impact beyond signaling which tribe the writer belongs to.

Here’s an inconvenient fact that might shock newsrooms who invoke “democracy” (looking straight at you, Washington Post) like a religious incantation: the word doesn’t appear in any of America’s founding documents.

Not in the Declaration of Independence. Not in the Constitution. The founders deliberately created a constitutional republic, with checks and balances and representative government, specifically because they feared the mob rule of pure democracy. Yet modern journalists invoke “democracy” constantly, as if repetition could make their political preferences sacred.

In fact, Democracy probably does die in darkness. But it’s buried deeper when you bastardize the word “democracy” day after day after day after day. Media need only look in the mirror to see the ones pulling the cord on the lamp.

The Respect Principle

The Seattle Times, like many legacy metropolitan newspapers, has been ideologically imbalanced for what is objectively a long time. Over the past 20 years, it went away – gradually but all at once, and now is quite possibly irretrievably gone.

This imbalance manifests not just in what some of these newsrooms cover (and those they intentionally omit), but in how they frame every story as a battle for democracy itself. They’ve worn out the word through overuse, turning what should be a meaningful concept into a partisan trigger.

At The Center Square, we’ve made a radical decision by measure of today’s news-media standards: we ban staff-generated opinion content. Completely. We don’t need reporters to lecture readers about democracy because we’re too busy showing them how their government actually works – and where, objectively, it doesn’t. We don’t need to invoke the founders’ vision because we’re focused on today’s budget realities.

Curiosity, rather than conjecture or conviction, should drive the news.

Every newsroom faces a fundamental choice: Speak with your audience or talk at them. When you constantly tell readers that every executive order, every legislative vote, and that every policy disagreement endangers our democratic norms, you’re not informing - you’re haranguing. You’re the boys and girls who cried wolf and, eventually, people stop listening.

But I believe many metro columnists are well beyond that point and are simply singing to their choirs.

The Erosion of Credibility Through Lecturing

The death of straight-news reporting didn’t happen overnight. It was a gradual surrender, one opinion piece at a time, one solutions-journalism lopsided advocacy story at a time, one “democracy in danger” headline at a time, until readers could no longer distinguish between actual threats and partisan hyperbole. The sky can’t fall every day.

When journalists transformed from reporters into democracy’s self-appointed guardians, they lost something essential: credibility. The founders understood that in a constitutional republic, the press serves the people best by informing them, not by telling them what to think. They created a system of representative government with enumerated powers and clear limitations – nowhere did they suggest that journalists should serve as democracy’s PR department.

Look at any major newspaper today. Stories that should be straightforward – a tax increase, a regulatory change, a budget vote – are wrapped in layers of democratic implications. Reporters don’t just tell you what the governor did; they tell you what it means for democracy. They’ve appointed themselves as constitutional scholars and moral arbiters, despite the fact that many couldn’t tell you (and make no effort to tell you) the difference between a democracy and the constitutional republic we actually inhabit.

This is what happens when newsrooms prize an ideology over information. The construction worker watching his or her property taxes rise doesn’t need another democracy lecture. They need to know where their money is going and what they’re getting for it. Small business owners navigating local or state regulations don’t require civics lessons from journalists. They need clear, factual reporting about what rules must be followed. They have a payroll to make, and never stop thinking about the families their business supports.

The Center Square Model: Show, Don’t Tell Democracy

Our stringent focus on straight-news reporting reflects a deeper understanding of how representative government actually works. The founders created a system where informed citizens could hold the elected and their bureaucratic staff accountable through regular elections and constitutional constraints. They didn’t envision a priesthood of journalists interpreting sacred democratic texts. They envisioned a free press that would report facts – and could, without fear of repercussion.

By banning staff-generated opinion content, The Center Square newswire honors that original vision better than outlets that wrap themselves in “democracy” while pushing partisan perspectives. We don’t tell readers that a government program threatens or strengthens democracy. We report what it costs, whom it serves, and whether it achieves its stated goals. Readers can decide for themselves what it means for representative government. The reader can decide on their own whether government action or inaction jibes with their life.

Our “Accuracy + Velocity + Frequency” mantra enforces this discipline. When you’re focused on getting accurate information to readers quickly and consistently, you don’t have time to pontificate about democratic norms. You’re too busy doing the actual work of accountability journalism: examining budgets, tracking spending, measuring results.

The Taxpayer as North Star

Living among the people teaches you that they understand our system of government better than many journalists. They know we live in a constitutional republic where their representatives are supposed to be accountable to them. They don’t need journalists invoking “democracy” every third paragraph. They need information about what those representatives are actually doing.

The plumber, the teacher, the farmer – they’re not confused about our form of government. Well, perhaps some K-12 public school teachers and college professors are, but many are not. Nonetheless, they elect representatives. They expect those representatives to spend tax money wisely. When that doesn’t happen, they want to know about it. Not through the lens of democratic theory, but through simple facts: How much was spent? What was accomplished? Who made the decision? How did my locally elected representative in government vote on the legislation?

This is why our ban on staff-generated opinion content matters. In a constitutional republic, a nation of laws, citizens need facts to hold their representatives accountable. Every opinion piece about democracy’s fragility is a missed opportunity to report on what government actually did today. Every column invoking the founders is time and physical publishing and broadcast space that could have been used to show taxpayers where their money went.

The Multiplication Effect

Our growth to 1,360 outlet partners proves something the democracy-obsessed media establishment doesn’t want to admit: Readers are tired of being lectured about “democratic” values and hungry for actual information about their government. They want news, not a sermon.

These partners span the entire political spectrum because facts about government operations transcend partisan democracy debates. When we report that a federal agency spent $50 million on a program that failed to meet its objectives, we don’t need to invoke democracy. The facts speak for themselves. Conservative outlets can use that information. Progressive outlets can use it. Those who consciously try to convey the news straight can use it. Taxpayers of all political stripes can use it to evaluate their representatives.

The word “democracy” has become so politicized, so overused, so stripped of meaning that it now divides rather than unites.

But everyone understands waste. Everyone understands accountability. Everyone understands results – or the lack thereof.

By focusing on these universals rather than partisan trigger words, we serve the actual functions of representative government better than outlets that cry “democracy” at every turn.

The Restoration of Trust Through Restraint

Here’s what Mr. Dudley and the Seattle Times, and frankly so many others, miss: You can’t save journalism by invoking democracy more cleverly. You save it by doing the work that makes representative government possible – providing citizens with accurate information about their government’s actions.

Dudley’s headline acknowledges the problem – “don’t say ‘democracy’” – but his solution is to say it anyway, just more strategically. This misses the point entirely. The word has lost its power not because of messaging strategy but because of overuse and misuse. When everything is a threat to democracy, nothing is. When every story requires democratic context, readers tune out and miss the facts.

The founders were precise with language. They created a constitutional republic, not a democracy, and for specific reasons. They wanted informed citizens making thoughtful decisions through their representatives, not mob rule driven by passion or the latest policy craze. Modern journalism’s obsession with “democracy” often serves passion over information, emotion over facts, tribal loyalty over citizen accountability.

At The Center Square, we don’t need to invoke democracy because we’re too busy serving its actual functions. Every story about government spending is a tool for accountability. Every report on program effectiveness is information citizens need. Every fact we publish serves the constitutional republic’s requirement for an informed citizenry.

The Seattle Times publishes approximately 15 opinion pieces defending democracy for every piece of original enterprise reporting showing what government actually does. They’ve cried wolf so often that when real threats emerge, who will listen? Meanwhile, the daily operations of government - the budgets, the programs, the regulations that affect real people - go underreported.

Democracy – or more accurately, our constitutional republic – thrives not when journalists constantly invoke it, but when they do the unglamorous work of reporting facts. With 1,360 partners and growing, The Center Square has proven that there’s a massive appetite for news that serves representative government through information rather than incantation.

The path back to trust isn’t complicated. Stop crying wolf about democracy. Start reporting what government does. Stop telling people what the founders would think. Start showing them what their representatives are doing today. Recognize that in a constitutional republic, the press serves best not as democracy’s PR department but as citizens’ information service.

Don’t lecture about democracy from the ivory tower. Serve accountability through originally reported facts from the ground up.

The founders would understand. More importantly, so do news consumers.